art of travel

What’s New

The Latest Product Updates from India

Compiled by Soma Paul, Product Manager, Destination Knowledge Centre

STAYS TO WATCH OUT FOR

New Hotels

- Virsa Baltistan, Turtuk, Ladakh

- Cavalry Villa, Bikaner, Rajasthan

- Anantara Jewel Bagh, Jaipur, Rajasthan

- Sadar Manzil Heritage by Atmosphere, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh

- Meru Van, Kanha, Madhya Pradesh

- Holdu Tola, Pench, Madhya Pradesh

- Gateway, Coorg, Karnataka

- Halli Berri, Chikmagalur, Karnataka

We Are Excited About

Virsa Baltistan, Turtuk, Ladakh

Seven years of patient work have shaped Virsa Baltistan — and every courtyard and mud-plastered wall seems to tell a story. Six hours from Leh, in Turtuk, one of India’s last villages before the border, this 12-room hideaway sits between the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges. Built the traditional way with clay, mud, and apricot pulp, it promises both strength and warmth. We can already imagine our guests enjoying slow meals by the river, stories from villagers, and stargazing sessions on the “mountain beach.

Cavalry Villa, Bikaner, Rajasthan

Some places feel less like hotels and more like walking into someone’s story — Cavalry Villa sounds exactly like that. Just a two-minute walk from the Bikaner station, it’s where Colonel Mahendra Singh has filled the rooms with memories of a life in uniform, while his wife Bhawna weaves in art, music, and charm. Seven rooms, sunlit courtyards, and a welcoming dog named Nawab waiting at the door — it’s the kind of place where stories find you before you even unpack.

Halli Berri, Chikmagalur, Karnataka

Set on a working coffee estate in the Baba Budan hills, Halli Berri is run by Nalima Kariappa and her three daughters — a family deeply tied to the land. It was on these very hills that Baba Budan, a 17th-century Sufi saint, is said to have first planted coffee beans smuggled from Yemen, changing the course of India’s coffee story.Two cottages, six breezy rooms with bay windows and sit-outs open to misty mornings and unhurried afternoons. Their Rainforest Alliance-certified coffee, grown using sustainable farming practices that protect the forest and its wildlife, promises to be a highlight. With over 260 species of birds and a few friendly dogs around, it feels like the kind of place where slowing down comes naturally.

EXPERIENCES TO WATCH OUT FOR

New Experiences

- Pahari Miniature Painting, near Shimla, Himachal Pradesh

- The Art of Pichwai, Jaipur, Rajastha

- Let’s Get Spicy, Mumbai, Maharashtra

We Are Excited About

Let’s Get Spicy, Mumbai, Maharashtra

Get ready to dive into Mumbai’s spice scene! From traditional recipes to connecting with a local family, this culinary journey promises to be a flavour-packed adventure. Imagine sampling authentic Mumbai coastal dishes while learning about the rich history behind every ingredient. We can’t wait for our guests to experience this aromatic side of Mumbai!

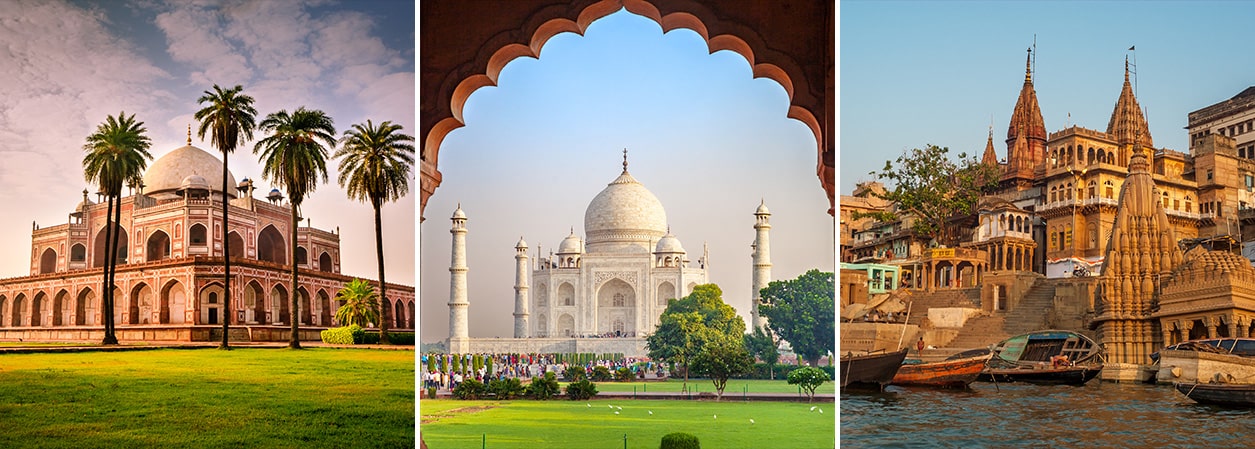

ITINERARY OF THE MONTH

Roots and Routes Less Travelled

Delhi – Jaipur – Karauli – Agra – Tirwa – Lucknow – My Mom’s Village- Varanasi – Delhi

Highlights of the Tour

- Dive into the hustle and bustle of Delhi, where history and chaos collide in the most fascinating way.

- Take a walk through Jaipur’s royal past, and explore its colourful bazaars.

- Go off the beaten path to discover small towns where time moves a little slower and life feels simpler.

- Head to Karauli — check out the City Palace, wander through the narrow streets, and visit the Kaila Devi Temple to see what local life’s really like.

- Stand before the Taj Mahal, and let its beauty remind you why it’s one of the world’s wonders.

- Meet locals, see how ittar is made (a traditional perfume from flowers, herbs, and spices), and take in the quiet charm of village life.

- Head to Lucknow, the “City of Nawabs,” known for its elegant architecture, mouthwatering Awadhi food, and old-school charm.

- Finally, experience the energy of Varanasi, where ancient traditions come alive and the city feels like it’s been around forever.

RESTAURANT TO WATCH OUT FOR

New Restaurant

The Cuisine Club, Jodhpur, Rajasthan

The Cuisine Club is Jodhpur’s new go-to for food lovers! Housed in a historic bungalow from 1934, it was once the estate house of the Patodi fiefdom in the princely state of Marwar. Just 10 minutes from Mehrangarh Fort and Umaid Bhawan Palace, it’s got that perfect mix of royal vibes and laid-back charm. They serve up authentic Rajasthani dishes, plus a diverse range of other options. We are excited about this new restaurant!

NEW FLIGHT

Bengaluru – Kochi – Bengaluru nonstop flights by Akasa Air

** Short on time? Connect Karnataka and Kerala effortlessly.

Time to Look Beyond the Usual

By Dipak Deva, Managing Director, Travel Corporation India Ltd.

For years, the Golden Triangle—Delhi, Agra, Jaipur—along with Varanasi, Kerala, and Rajasthan’s forts and palaces, have consistently captured the imagination of our overseas guests. These iconic destinations have helped put India on the global tourism map, and rightly so.

But I believe the time has come to consciously shift some of our focus beyond them.

Our Role Is Not Just to Follow Demand, But to Shape It: As India’s biggest Destination Management Company, we are not mere facilitators of travel. We are curators of experience. We must create aspiration, not just respond to it.

It is a Matter of Responsibility: Many of our best-selling destinations are reaching a tipping point. Local communities are bearing the brunt, resources are strained, and heritage is under pressure. By distributing footfall to less-frequented regions, we support balanced growth and contribute to a more equitable tourism economy.

The Next Chapter of Indian Travel Is Waiting: Whether it is living cultural heritage of Northeast India, the textile and craft stories of Gujarat, or the spiritual pluralism of places rarely mentioned in guidebooks—we are surrounded by powerful, immersive experiences that haven’t yet had their moment. But they will. If we champion them. We recently opened an office in Darjeeling to strengthen our presence in the Eastern Himalayas—a region rich in Lepcha, Bhutia and Nepali traditions, colonial tea heritage, forested trails, and sacred landscapes. Still underrepresented in most itineraries, its stories deserve a larger stage.

Our best-selling destinations will always be part of our story. But if we want to keep inspiring the world to come to India—and come back—we must keep evolving.

That means discovering the undiscovered, and curating journeys that surprise even the most seasoned traveller.

Because when it comes to India, there is always more to tell. And we are the ones who must tell it.

Stories from India

The Syrian Christians of Kerala

By the Research Hub, Destination Knowledge Centre

The Syrian Christians of Kerala are one of the oldest surviving Christian groups in the world. Not many know this, but Christianity arrived in Kerala around the same time it reached Europe. The first converts, as early as the 5th century, were high-caste Hindu Brahmins — the priestly class — and many of their traditions still live on in the community even today. It’s this unique lineage that sets Syrian Christians apart from other Christian groups in India, who were converted much later by European missionaries.

Culturally, they can be described as Hindu in tradition, Christian in religion, and Syro-Oriental in worship. Their church rites come from the Levant — what’s now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, and parts of Turkey near the River Euphrates.

Stories of St Thomas, one of Jesus’s apostles, still live on in their traditions — like in the Margam Kali, a beautiful dance where seven women, representing the apostles, circle a tall oil lamp while singing songs of praise.

It’s said that St Thomas landed in Kerala, sometime in the 5th century, sailing down the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. Interestingly, while most apostles faced persecution elsewhere, St Thomas was welcomed and allowed to preach freely in Kerala.

Syrian Christian families are famously close-knit — a web of marriages connects them much like the Rajputs of Rajasthan

Even the way they name their children is fascinating. Every family carries a name that might reflect an ancestor’s profession, a place, or even something whimsical. Take Pallivathukkal, for example — it means “at the church gate,” because centuries ago, that family had settled near a church.

Naming follows a beautiful order: the firstborn is named after the paternal grandparent, the second after the maternal grandparent, and the second name comes from the father. So, for instance, Bobby George would mean Bobby (grandparent) George (father). But he’s not really “Bobby George” until the family name is added — Bobby George Pallivathukkal.

It’s almost like a clan, and in the old days, large family gatherings were frequent, filled with prayers, storytelling, and of course, wonderful food.

The culinary traditions of the Syrian Christians have their own unique identity. Their kitchen took in influences from Arabs, Chinese, Malays, Portuguese, and Syrians who came to Kerala to trade spices. Dishes like Erachi Olarthiyathu (fried beef), Meen Vevichathu (fish curry cooked in a clay pot), Meen Moilee (fish stew), Nadan Tharavu Curry (duck roast), Ethakka Appam (plantain fritters), and Kozhukatta (stuffed rice cakes) are absolute Syrian Christian classics.

Back in the day, a Syrian Christian kitchen would have four to six wood-fired stoves, their heat adjusted by the amount of firewood used. There were separate rooms for storing large utensils, coconuts, dried wood, and food staples. Spices and chillies were crushed by hand using a stone mortar and pestle. The big pots were scrubbed in deep stone sinks in adjacent rooms.

And no kitchen was complete without the Cheena Bharani — a ceramic jar where homemade pickles and yoghurt were stored. (“Cheena” means China — a nod to the Chinese traders who reached Kerala a full century before Vasco da Gama did in the 15th century)

A cooking class of Syrian Christian Cuisine is highly recommended during a Kerala holiday. Get in touch with your relationship manager for more details.

Sustainability and Us

The Morungs of Nagaland: Lessons in Wisdom and Sustainability

By Kuntil Baruwa, Explorer, Destination Knowledge Centre

The Morungs of Nagaland may not have the same shine they once did, but they’re far from forgotten. These institutions were once central to village life, and though they’ve faded in many ways, the lessons they taught still hold strong.

In their prime, Morungs were more than just dormitories for young men. This is where boys became men. It was a space where they learned to live together, respect each other, and understand their role in the community. From a young age, they were taught lessons in both practical and moral living—preparing them for life in harmony with their surroundings. These teachings were rooted in a deep sense of sustainability, both for the environment and the community.

Naga author Easterine Kire Iralu captures the essence of these teachings in A Naga Village Remembered:

“If you are at a community feast and take more than two pieces of meat, shame on you. Others will call you a glutton; worse, they will think, ‘Has no one taught this boy about greed?’ This is the key to right living—avoiding excess in everything. Be content with your share of land and fields. People who move boundary stones bring death upon themselves.”

These words highlight a culture of moderation and respect. In the Morung, young men learned to reject greed, value fairness, and protect shared resources—lessons that are still relevant today. In a world that often encourages excess, this approach offers a quiet but powerful guide for sustainable living.

The Morung was also the village’s cultural and spiritual centre. It held everything from weapons to art and craft, and was where important rituals were performed and decisions were made. Iralu writes:<

“The full moon was declining, and on the decline of the full moon, the ritual of making peace with the spirits was held. ‘We have come to solicit peace between man and spirit. Let there be no destruction and calamity, no death and disease and plague. Who is honest, you are honest. Who is honest, I am honest. We will compete with each other in honesty.'”

These rituals reflect a deep belief in balance—not only between people but also with the spirits and the land. Practices like these, rooted in gratitude and accountability, offer a reminder that sustainability is not just about the environment, but about maintaining balance in every aspect of life.

While the Morung may no longer be as central as it once was, its spirit lives on. It stands as a reminder of the values that support sustainable living—moderation, respect, and community. As we face the challenges of today, the lessons of the Morung still offer a valuable guide, reminding us that the past has much to teach us about creating a balanced future.

About Easterine Kire Iralu:

Easterine Kire Iralu is a poet, writer, and novelist from Nagaland, widely regarded as one of the finest storytellers from Northeast India. She has written several books in English, including collections of poetry and short stories. Her novel, “A Naga Village Remembered”, was the first-ever Naga novel to be published. Iralu’s works provide a rare glimpse into the lives of the Naga people, whose culture is almost unknown to the wider world. She addresses the complexities of colonial atrocities, in-house rivalries, and ideological differences among the Naga brethren fighting for freedom. Through her extensive collection of writings, she has brought the largely unspoken and deeply rooted Naga traditions to the world, uncovering age-old practices and folklores from the remote corners of Nagaland.

Explore

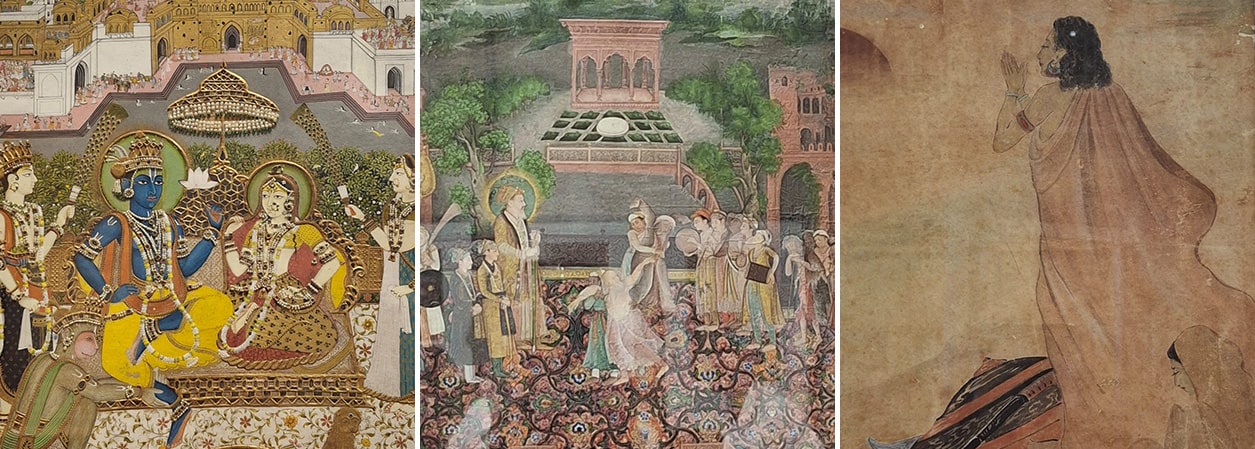

Wandering Through Time at the Indian Museum’s Art Gallery

Miniatures, rebellions, and the quiet music of brushstrokes in the heart of Kolkata

by Kuntil Baruwa, Explorer, Destination Knowledge Centre

This was my first visit to the Art Gallery section of the Indian Museum in Kolkata, and it felt like I was stepping into a conversation that has been going on for centuries. Of stories told in line and colour. Of philosophies, rebellions, love affairs, and lullabies. And if you listen carefully, they have a lot to say—not just about Indian art, but about Kolkata itself.

The gallery itself had its quirks. Balding, middle-aged museum staff snoozed peacefully on plastic chairs in the corners, undisturbed by time or tourists. Meanwhile, the security personnel at the entrance were all sharp eyes and checklists—paranoid about compliance. It was a contrast that somehow felt very Kolkata—chaos and order, indifference and intensity, all coexisting under one colonial roof.

You see, this city wasn’t just a capital during the British Raj—it was a cultural crucible. Even my favourite poet, Mirza Ghalib—famously hard to please—once said: “Calcutta is the mirror of Hindustan.”

Take the Bengal School of Art, for example. Born right here in the early 20th century, it wasn’t just an art movement—it was a quiet rebellion. A group of artists, led by Abanindranath Tagore, who decided they had enough of mimicking the West. Instead, they dipped their brushes into Indian tradition, Persian styles, Buddhist frescoes, Japanese wash techniques, and their own lived realities. The result? Works that were gentle but defiant—paintings that didn’t shout, but lingered. They gave Indian art a new confidence. And in doing so, they gave Bengal one of its proudest intellectual legacies.

And then there were the older rooms—home to the miniature paintings, where you could lose hours without realising. You are surrounded by centuries of meticulous brushwork—jewelled little windows into different worlds.

There is the Mughal school—refined, imperial, full of realism and grandeur. Court scenes, battles, lovers in pavilions under starry skies. Persian influence meets political power here, and every detail is rendered with such care, it draws you in like a secret. In one painting, I found something unexpected: Emperor Akbar, known for his syncretic spirituality, depicted worshipping the sun. A moment of quiet reverence that somehow made the grandeur more human.

Then there is the Rajput school—bold, bright, and utterly unapologetic. These were made for the princely states of Rajasthan. The colours leap out at you—saffron, vermilion, peacock green—and the themes are often epic: Krishna’s divine play, heroic battles, stormy monsoons. It’s as if the desert kingdoms painted their inner worlds in defiance of the arid land outside.

The Pahari miniatures, from the hills of Himachal and Jammu, are softer—lyrical and romantic. There is a kind of musicality to them. Delicate lines, flowing forms, Radha and Krishna in quiet glances or coy gestures. They feel like visual poetry set to the music of the flute.

The Deccani school, from the courts of Bijapur, Golconda, and Hyderabad in south-central India— took me by surprise. Deep, saturated colours. Stylised figures. A kind of otherworldly mysticism. It was here that I stumbled across something that truly mesmerised me—a painting of Raag Megh Malhar. A man and woman entwined on a terrace, bow in hand, monsoon clouds rolling in above them like a celestial drumroll. It was part of the Ragamala series where each raga— melodic notes in Indian classical music—is personified. And even though there was no sound, I swear I could hear the music in the paintings. It was visual melody. I just stood there, rooted, as if they were humming to me in a language I didn’t know I knew.

That is the thing about Indian art—it is never just about what you see. It is about what you feel. What you remember. What you didn’t know you carried.

And in a city like Kolkata, where music and poetry spill onto the streets, where art is debated over tea in crumbling cafés, where rebellion and refinement walk hand in hand—it makes complete sense that a museum like this exists. It doesn’t just preserve art. It preserves imagination.

So, if you are ever here, do visit the Art Gallery of the Indian Museum. Let the miniatures pull you into their stillness. Let the Bengal School’s gentle rebellion remind you that art can be political without ever being loud. And if you see Ragini Megh Malhar again—framed against those thunderclouds—tell her I said hello.

Inspiration

The Grasshopper’s Run by Siddhartha Sarma

Campfire Review by Kuntil Baruwa, Explorer, Destination Knowledge Centre

You don’t often come across a novel like The Grasshopper’s Run.

Just about 200 pages long, but it’s packed with a world few people even know existed — the misty, battle-scarred hills of Northeast India during World War II.

Most people don’t realise that some of the fiercest, bloodiest battles between the Japanese and the Allied Forces were fought there. It was on these hills that the Japanese were beaten back for the first time in the Asian theatre — and that changed the course of the war.

That’s the backdrop Sarma drops you into. But this isn’t just another war story.

It’s also a deep dive into the oral traditions, legends, and wisdom of the tribes of Northeast India.

Like this line that stayed with me:

“When you hunt, you are placing your hunger against the animal’s desire to live. If your hunger is greater, you will get the animal. But not always.”

At the centre of it all is Gojen Rajkhowa — fifteen years old, Assamese — but no ordinary boy.

He’s been trained in a morung by the Ao Nagas, one of the sixteen major Naga tribes.

The morung wasn’t just a dormitory back then. It was a school of life.

Boys learned survival, loyalty, wit — everything needed to carry forward the spirit of the tribe.

They were taught to be sharp without being deceitful.

The Grasshopper’s Run is about Gojen’s brutal journey into the unknown, tracking down the Japanese General who ordered the massacre of a Naga village — a massacre that took Uti, Gojen’s closest friend, the brother he chose.

But as Gojen’s journey unfolds, you realise it’s not just about revenge. It’s also about stepping into an ancient legend — the legend of the Grasshopper of the Ao Nagas:

“You can burn me now, Fire. The Grasshopper will come looking for you.”

One of the reasons the story feels so alive is Sarma’s obsessive attention to detail.

He travelled to Myanmar just to test-fire the Lee-Enfield Mark III rifle, the same one Gojen carries.

He spent months pouring over the Battle of Kohima, visited the Imperial War Museum in London, studied Japanese uniforms at the Assam State Museum, and cross-referenced terrain maps drawn up by JP Mills, one of the few British administrators who actually understood the tribes.

Sarma didn’t just research the world — he walked through it.

And you can feel that when he describes a massacre scene with lines like:

“The steady liquid clack-clack of heavy Nambu machine guns gave a finality to the matter.”

What really lifts the book, though, is the way Sarma gets inside the heads of his characters.

Gojen, of course. But also, others like Lt. Colonel Kenneally of His Majesty’s Intelligence Corps — a man neck-deep in the Great Game, who helps Gojen by identifying the Japanese General Shunroku Mori, the butcher of Nanjing, the man responsible for Uti’s death.

And then there’s General Kotoku Sato — senior, seasoned, and yet helpless against Mori, the psychopath who somehow holds the key to Japan’s plans in India.

Sarma even sketches Mori’s twisted roots — the slow learner bullied at school, the boy who raged at his own helplessness, who hated his brilliant elder brother who was the teachers’ favourite.

Nothing here is black and white. Everyone carries their own shade of grey.

At the end of it, The Grasshopper’s Run is a story about friendship, honour, survival, revenge, courage, grief — and the heavy shadows war leaves behind.

The kind of story that lingers long after the last embers die down.

A Campfire Review is a way of talking about a book not like a formal critic, but like an explorer or traveller sharing a story by the fire with anyone willing to listen — candid, personal, and focused on what stays with you long after the last page. It’s less about analysing and more about passing on an experience.

Festival to Watch Out For

Hemis Festival, Ladakh

5th – 6th July 2025

The Hemis Festival is a two-day celebration in Ladakh that honours Guru Padmasambhava, who brought Tantric Buddhism to the Himalayas. It all comes alive in the courtyard of Hemis Monastery — the biggest monastery in Ladakh — on the 10th day of the Tibetan lunar month.

Locals turn up in their finest traditional clothes, and the monks put on an incredible show of masked dances and sacred plays, with drums, cymbals, and long horns filling the air. A colourful fair, full of beautiful handicrafts, adds to the buzz.

One of the highlights is the Chaam dance. Monks, wearing fierce masks, re-enact the victory of good over evil. As part of the ritual, a dough sculpture — symbolising demons — is sliced apart with a sword, burnt, and its ashes scattered to purify the soul after death.

Hemis is about an hour’s drive from Leh. If you’re planning to visit, we recommend staying at Shel Ladakh, a cosy 3-bedroom homestay in Shey village, just half an hour from Hemis. It’s the kind of place where you wake up to views of the mountains and a slower, gentler rhythm of life.

For more details, reach out to your relationship manager — they’d be happy to help you plan this special experience.

RESOURCES

SITE LINKS

CONTACT US

+ 91 (124) 4563000

Tower B, Delta Square, M.G. Road, Sector 25, Gurgaon - 122001, Haryana, National Capital Region of Delhi, India