art of travel

Monthly Musing

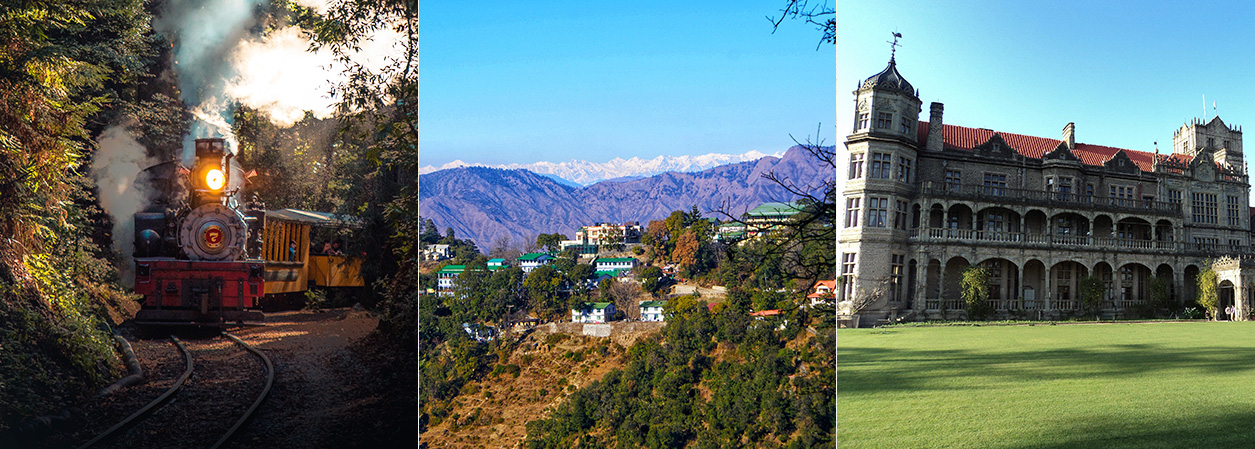

India’s Hill Stations: From the British Raj to Tourist Attractions

The hill stations of India with their cooler climes and incredible landscapes set against stunning mountain backdrops have been serving as a refuge from the scorching summers since the early part of the 19th century. They were created as health–cum–vacation resorts for the European gentry who were exposed to frequent outbreaks of malaria and cholera in the tropical plains during summer. A cure was yet to be found which caused a high level of mortality. Whilst doctors sent their patients recovering from illness to resorts on the French Riviera and in the foothills of the Pyrenees during the bleak winter, the Europeans living in India headed to the hill stations to escape the heat and the tropical diseases.

Very interestingly, the early developers of these hill stations who enticed investors and the elite alike were British Army officers, administrators of newly conquered territories of the British East India Company, military doctors, businessmen, suppliers to the British Army, and European Tea and Coffee Planters. The hill station of Mussoorie, for example, which became famous as the “Ramsgate of the Himalayas” was founded by Superintendent Shore of the Doon valley, Captain Young, the commander of Landour cantonment, and an English businessman who opened a brewery for the British Army. The arrival of prestigious representatives of the British Raj, such as the Governor General of India to the hill station of Shimla in 1827, brought further fame to this pan-India colonial project, just like the members of the royal families did for the European resorts.

These developers who were strongly invested in the idea of European settlements in the hills even built their own residences and invited the European elite to spend the summer with them. Frenchman Jacques Mont wrote sometime in the early 19th century, “Isn’t it strange to dine in silk stockings in such a place, to drink a bottle of hock and champagne every evening, to have delicious mocha coffee and receive Calcutta Journals every morning?” He was in Shimla, then a settlement of no more than fifteen hamlets, as a guest of Captain Charles Pratt Kennedy, the newly appointed British Political Agent. The House of Gorkha of Nepal who had been on a collision course with the British East India Company over the trade route to Tibet were driven out and the control of this region was transferred to Maharaja of Patiala, who allied with the British during the war as a reward. Apart from health considerations, the hill stations also had their strategic military functions given their location on high ridges. From here it was possible for the British Army to check both the plains and the Himalayan borders.

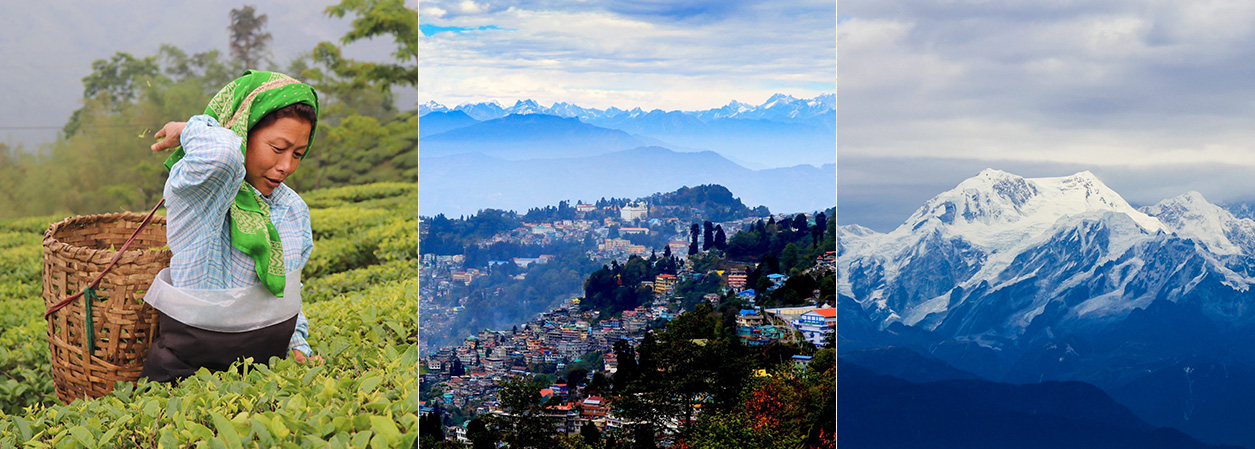

Darjeeling is a perfect example of how the hill stations of India were planned and structured

The Mall on the main ridge served as the axis of a hill station. With benches and kiosks, this tree-lined promenade connected the various European wards with their charming residential cottages and hotels. Observatories were set up at the summit of the highest ridges and hills that offered panoramic views. This was done both for leisure and strategic reasons. From the Observatory Hill in Darjeeling, one can enjoy a stunning sunrise over Mt. Kanchenjunga on a clear day minus the crowd of Tiger Hills. It is also the site of the Mahakal Temple, revered by both Hindus and Buddhists. This is from where the story of Darjeeling or Dorjé-ling, “the place of the thunderbolt” began. Shops, churches, banks, post offices, assembly rooms, libraries, gymkhanas, clubs, and playgrounds were all built at the edge of the Mall. The Military cantonments and the bazaars that provided supplies were located outside the Mall area. The settlements of the Indians who served the gentry were even further.

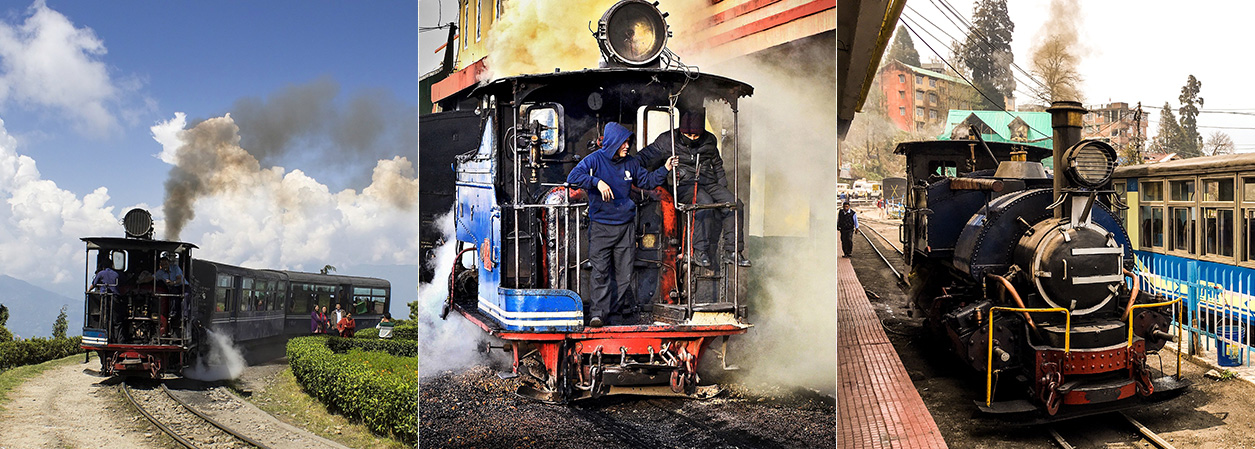

From the mid-19th – century onwards, the hill stations of India witnessed very interesting times that led to their diversification. The use of purified quinine which facilitated correct dosing to treat Malaria was a breakthrough during this period. There was an unprecedented rigour in the efforts of the British Raj to distribute and enforce the consumption of quinine. Systematic planting of Cinchona initially started at Ootacamund (present Ooty) followed by Darjeeling and Sikkim. And gradually, it became the economic backbone of the hills where cinchona plants were integrated into the wider colonial plantation economy. The now famed Darjeeling Himalayan Toy train which chugged up and down the hills of North Bengal was used in transporting the bark of Cinchona plants to manufacture quinine. This progress in the treatment of Malaria meant that long stays in the hill stations were no longer required. But in spite of this, doctors continued sending their patients, particularly women, and children, to the hill stations to recover. Keeping with Victorian ideology and social Darwinism to produce the strong men that the Empire needed to rule India, this was also the time when a lot of boarding schools were established in the hill stations.

Post the Great Indian Mutiny of 1857, many hill stations became British Army headquarters and summer capitals for civil administration. The remote locations of the hill stations proved to be of great advantage while sheltering women and children during the Mutiny. As a result, there was a large influx of the British civil and administrative elite from the big cities of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras to the mountainous periphery of the Empire with their entourage of Indian servants. They were all housed in the crowded bazaars located below or at quite a distance from the English wards. Towards the end of the 19th century, the colonial project of the hill stations witnessed a new entrant which put to an end the British claims of exclusivity on the hill stations of India – the Maharajas and the princes of India who built their summer castles, bungalows, and manors despite the opposition of the British gentry. They were soon joined by rich Indian businessmen who purchased properties in the English wards not only as their summer residences but also for rent to European holidaymakers. They also built hotels that catered only to the Indian elite who would come on holiday and spend time with their children studying in the boarding schools. Socialising and recreation in the hill stations progressively took over from what started off as health–cum–vacation getaways from the tropical maladies during summer a century ago.

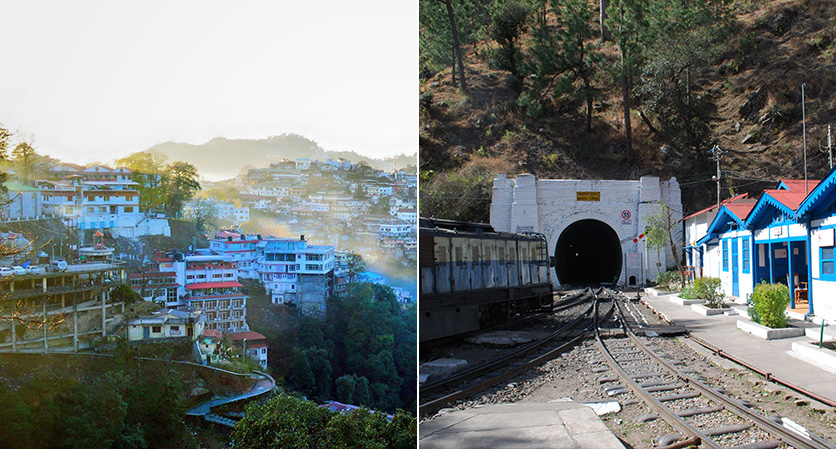

With Shimla becoming the summer capital of the British Raj at the beginning of the 20th century, socialising and recreation soon gave way to decadence. Here is an excerpt from a letter written by a British gentleman to his mother from Shimla – “Last night I went to a ball given by the German Consul who is the richest man in Simla and gives the best entertainments. The narrowness of the space rather prevented me from showing off my fine stride but I did not get very much bored, which is generally the best I can say of a ball. Thursdays I am going to Viceroy’s for a dance and I am afraid I shall get entrapped for several others”. Soon after, Kalka in the plains was connected to Shimla by what is now the Kalka-Shimla toy train passing through quaint stations with stories legends are made of. At about the same time, Madras (now Chennai) was connected to the hill station of Ootacamund (now Ooty) by the present-day Nilgiri Mountain Toy train.

India’s independence in 1947 resulted in the hill stations of India losing their shine temporarily, although the Indian elite who assumed the leadership of the country after the departure of the British continued their sojourn in the hills every summer and joined their children studying in the boarding schools during holidays. But the hill stations made a strong comeback with the formation of new states and many became state capitals such as Shimla, Dehradun etc. With the emerging middle class of the 1960s starting to travel, the hill stations no longer remained exclusive to the elite of Indian society. Bollywood on its part played a great role in popularising the hill stations in the public imagination. “Mere Sapno Ki Rani” from the film Aradhana (1969) is still considered to be one of the most romantic songs to be shot on a train, the Darjeeling Himalayan toy train in this case, while the more recent film Barfi (2012) is shot across many picturesque locations in Darjeeling.

Today, if the elites of India have villas and bungalows in the hill stations where they holiday in the summer with their retinue of servants just like the British did before them; there are also all categories of hotels, from the very simple budget guesthouses to the more swanky ones, some from the colonial age, scattered across all the wards. The romance of the hill stations continues!!

Explore

Darjeeling Our Way

DAY 1: ARRIVE DARJEELING

Go for a leisurely stroll in the afternoon on the Mall Road (no vehicle zone) with a storyteller. Listen to the many stories of Darjeeling, visit iconic institutions such as the Darjeeling Gymkhana, and meet interesting locals. End your day with a visit to the Himalayan Tibetan Museum, a hidden gem which is a community-based initiative. All monies spent here go back to the Tibetan community. Guests may opt to browse through the collection at Hayden Hall which is a fair trade shop started by Fr. Edgar Burns, a Canadian Jesuit in 1969 to empower the local women of Darjeeling.

DAY 2: IN DARJEELING

Enjoy the magnificent views of Mt. Kanchenjunga during sunrise from the viewpoint at Chaurasta. Continue with the storyteller to the Mahakal Temple, revered by both Hindus and Buddhists, where the story of Darjeeling began. Post breakfast, head to the Darjeeling Railway Station and listen to the stories of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway followed by a quick visit to the replica of Nepal’s Pashupati Nath Temple located nearby the station. Take the Toy Train from Darjeeling to Ghoom with the storyteller. From Ghoom continue to a village located inside a wildlife sanctuary (cycling to the village is also possible for active guests). Walk around the village, interact with the villagers, and enjoy a simple home-cooked lunch. The tour ends with a performance by the Gadharva Brothers, farmer-musicians who are keeping alive the oral traditions and stories of the Himalayas despite the many challenges.

DAY 3: IN DARJEELING

Visit the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, the Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park, and the Tibetan Refugee Centre, a centre of art and craft. Continue with the storyteller to the Ging Tea Estate. Walk around the tea garden; interact with the workers, and visit the factory to see how tea is processed which will be followed by a private tea-tasting session. Lunch today will be authentic Nepali cooked by the Chef of the Ging Tea Estate.

DAY 5: DEPART DARJEELING

Continue to your onward destination

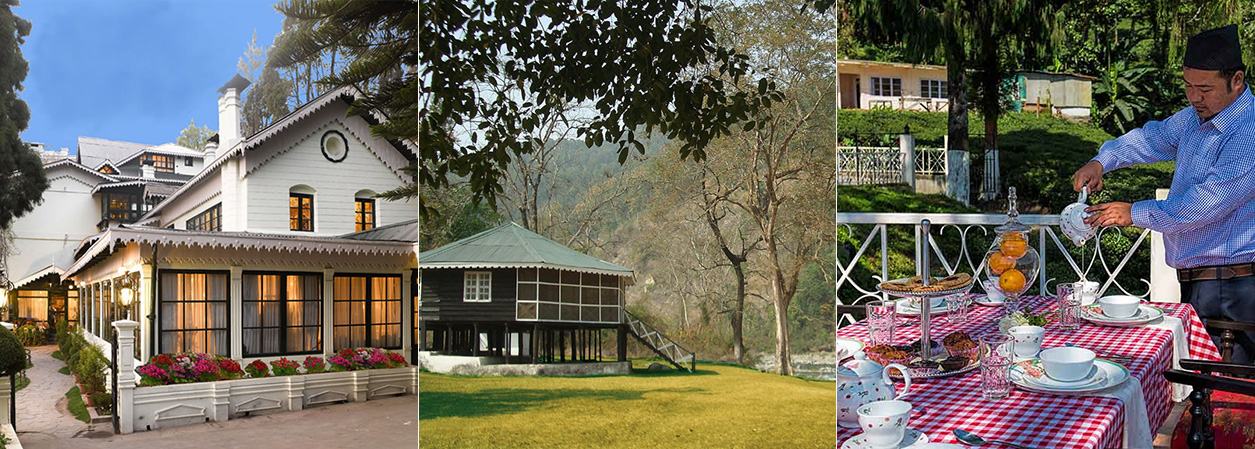

Where to Stay

The Elgin

Originally built in 1887 as the summer residence of the Maharaja of Cooch Behar, The Elgin is a charming thirty-five-roomed heritage hotel in the heart of Darjeeling town. The hotel has been extensively refurbished to preserve its former grandeur and its history has been kept intact. The comfortable rooms are furnished with wooden floors, vintage teak furniture, and splendid views of the mountains and valleys. It is the ideal starting point for exploring spectacular mountain peaks, pine forests, and historic monasteries. With cosy décor, crackling fireplaces, candle-lit tables, classical music played on the grand piano, and discreet waiters in uniforms, The Elgin offers a chance to get acquainted with the many charms of the Darjeeling Hills. They also serve special high tea from the world-famous tea gardens of Darjeeling at the lounge. A well-stocked library, cultural performances, and many opportunities for nature walks make this heritage hotel a perfect destination for 3 nights.

Glenburn Tea Estate

A tea plantation retreat perched on a hillock above the banks of River Rungeet overlooking the mighty Kanchenjunga Mountain range. Established in 1859 by a Scottish Tea Company, the estate is located an hour and a half drive from Darjeeling. The estate has two bungalows, the 150-year-old Burra Bungalow and the Water Lily Bungalow, facing each other and offering breathtaking views of the Darjeeling town and the Kanchenjunga Range. Each bungalow consists of four rooms decorated with antique furniture and Burma teak flooring. If guests are interested in some adventure, then there is also the Glenburn lodge which is a simple log cabin at the bottom of the estate overlooking the river. Breakfast and lunch are served on the verandah or in the gardens. Dinner is usually served in The Dining Room, where the hosts and guests in residence from across the world congregate to share stories and engage in lively conversations. Guests can choose from a range of hikes that can be curated to their requirements. There are opportunities to go fishing, bird watching, interacting with the in-house chef while learning how to make a meal, or just enjoying a picnic in a scenic location. It is recommended to stay a minimum of 3 to 4 nights to unwind as it is quite a journey to get to this beautiful bungalow located in a remote area.

Ging Tea House

One of the oldest tea plantations in and around the hills of Darjeeling, Ging Tea House was built in 1864. The Tea House is said to be one of the earliest colonial tea planter bungalows of the region. Situated half an hour’s scenic drive from Darjeeling town, the plantation hideaway is set on top of a hill amidst 960 hectares of the lush green tea estate. The colonial bungalow was restored sensitively to keep intact the heritage structure; rafter ceilings, teak wood flooring, four poster beds, and antique furnishings. Six distinctively designed suites with spacious bathrooms and all modern amenities make up the stay options. The multi-cuisine menus feature local, Indian, and continental meals that are prepared with seasonal fresh produce with plenty of ingredients sourced from their own organic kitchen garden. The spacious communal dining room is apt for extended lunches, dinners, and great conversations. The simple touches such as pampering guests with bed teas, four-course sit-down dinners, and staff in-waiting at all times, go a long way towards making the experience memorable. The Tea tour allows you to see, pluck, taste, and experience Darjeeling Tea first-hand before the tea-tasting session fully awakens your senses. There are plenty of hikes to choose from, as well as rustic planters’ picnics and bonfires with live music, and local dance performances for evenings. A minimum of 3 nights is recommended for a perfectly rejuvenating experience.

Guest Column

Toy Train to the Clouds

By Paul Whittle, Vice Chairman, Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Society, UK

The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (DHR) is truly world famous. For almost 142 years the little British-built steam locos have been climbing over 7,000ft up to the hill station of Darjeeling. Built in the days of the British ‘Raj’ the 55 mile narrow gauge DHR opened in 1881, rapidly transforming the economy of the region. Up the line went foodstuffs, coal and machinery. Down the hillside went the output of the ever-expanding tea estates for export around the world. Not for nothing is Darjeeling’s famous brew still known as the ‘Champagne of Teas.’

Perhaps the DHR’s ‘finest hour’ was during World War 2 when it carried thousands of Allied troops to and from Darjeeling that had become a massive leave centre. There was even a specially constructed ambulance train that ran non-stop up the line conveying sick and wounded service personnel to the military depots at Lebong and Jalapahar.

Yet despite its current fame, less than thirty years ago the DHR was threatened with closure. Indian Railways was modernising fast and the old steam trains did not form part of their agenda. Fortunately, in the nick of time, supporters in India and around the world started a rescue campaign, and in 1999 UNESCO awarded the line World Heritage Site status – only the second to get that coveted accolade.

Keeping this twisting, turning steeply-graded line in operation has always been a challenge. A series of innovative reverses (or zig zags) and spirals eases the gradient, but the annual monsoon rain in this mountainous region calls for constant vigilance and sometimes expensive repairs. Yet to its credit, Indian Railways has risen to the task and invested much effort and expertise, maintaining the line’s unique heritage whilst providing a safe, comfortable journey experience. So alongside the vintage steam locomotives can be found a small fleet of diesel locos, whilst the recent introduction of modern air-conditioned carriages is proving very popular on the longer rides.

Today the DHR continues its major contribution to the local tourist economy and each year it carries well over 100,000 passengers, most opting for the round trip from Darjeeling to Ghoom via the splendid view-point at Batasia with its imposing Gurkha war memorial and the majestic background of the Himalayas.

Yes, steaming to Darjeeling really is one of the world’s great train rides!

Further information:

DHR Official web site: www.dhr.in.net

DHR Society UK: www.dhrs.org

Paul Whittle:pro@dhrs.org

Sustainability and Us

Baithak in the Hills – Musicians in Residence

Sharan Gandharva and Ramesh Gandharva a.k.a the Gandharva Brothers from Kachankawal village of the Jhapa District in Nepal travel miles by cycling, walking, and taking a few public means of transport to commute to Darjeeling. Otherwise, farmers from the fertile plains of Nepal, these two folk musicians perform well-loved Nepali songs with their ever-loved companion, Nepali Sarangi. Made of sturdy jackfruit wood, and polished with silk-smooth pine resin, the Nepali Sarangi bear the symbols and impressions of ancient string instruments that evolved over thousands of years across the Silk Route. Once the symbol of an idiosyncratic culture and musical tradition, their music is now endangered and fast vanishing in the cacophony of mainstream Nepali Music. With stories of beautiful villages, silk trade, and a regular dialogue of love, their music stimulates one’s curiosity and is a deep soulful journey. Breaking away from the regular, they come with music taught to them by their forefathers. Never burdened with their existential struggle, they worship music as a way of life.

Baithak in the Hills – Musicians in Residence celebrates the life and times of the Eastern Himalayas through music. This unique programme is organised and curated

by Darjeeling Walks for inquisitive savvy travellers in the remote villages of the Darjeeling Hills.

Objectives of the Baithak in the Hills – Musicians in Residence are –

Dialogue

To establish a dialogue between the oral traditions of the diverse music scenes of the Eastern Himalayas, the lesser Himalayas, and the institutionalised customs, practices, documentation of local music, and its history.

Tourism

To organise responsible tourism activities targeting a niche group of audience weaved around the Musicians and their stories.

Artists Residency

To build a collective of artists and enlist their music in a digital library for music and culture enthusiasts.

Economics

To connect the economic interests of the Musicians, their families, and livelihoods with the vast demographics of opportunities, e.g., tourism markets, art restoration projects et al.

Direct and indirect Art produce

To create collectibles themed on the Musicians, rare musical instruments, gestures, origins, and transform them as souvenirs to educate travellers.

Social Integration, Literature, and Research

To document the storytelling of the Musicians, their history, and conversations while they are performing and to compose an ethnographic research study.

Write to your relationship manager to know more about how you can include this unique programme in a Darjeeling itinerary

RESOURCES

SITE LINKS

CONTACT US

+ 91 (124) 4563000

Tower B, Delta Square, M.G. Road, Sector 25, Gurgaon - 122001, Haryana, National Capital Region of Delhi, India